FORSYTH COUNTY -- Patrick Phillips heard of the racial cleansing that occurred in Forsyth County in 1912 that was sparked by the rape and beating death of a white woman and lynching of an untried black suspect on the Cumming square, but not from his history books in school. He heard of the night riders who shot into homes, burned churches, hurled rocks through windows as myths and legends. The kinds of stories kids tell.

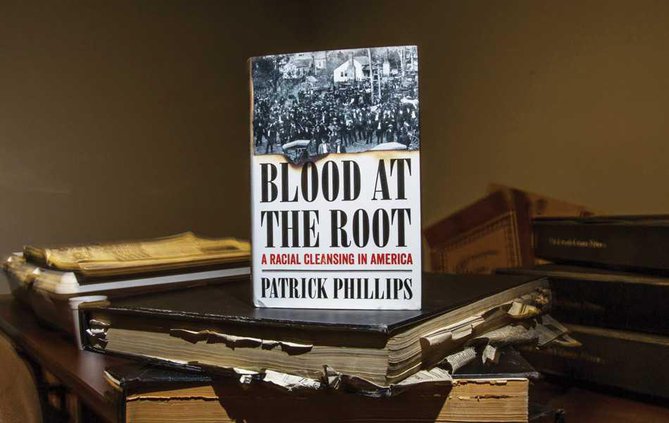

Author who grew up in Forsyth pens book on county’s history of racism