In 1809, Cherokee Chief James Vann was killed by still-unknown assailants at Buffington’s Tavern in the northeastern corner of Forsyth County and afterward was buried in a nearby, unmarked grave.

Vann was buried in Forsyth County’s Blackburn Cemetery, where Vann and about 250 others were buried from the 1800s until the final burial in 1909.

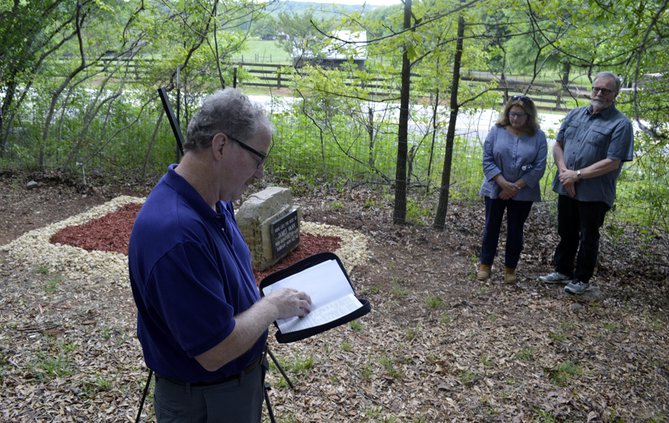

More than two centuries after his death, Vann’s grave was recently marked with a permanent stone, along with some graveside words and reading of scripture.

Who is James Vann?

• The Cherokee Indian leader and businessman was born February 1766 in Chatsworth and died Feb. 19, 1809 in Forsyth County.

• Vann was killed at Buffington’s Tavern in the northeastern corner of Forsyth County and buried at Blackburn Cemetery in a previously unmarked grave.

• Vann was known for owning and operating a number of taverns along Federal Road, which ran from Augusta to Chattanooga. One of the taverns can still be seen at the Cumming Fairgrounds.

On Saturday, the Historical Society of Cumming/Forsyth

County held a ceremony commemorating a marker placed Vann’s grave.

“We don’t know if Vann ever had a service, but we’re just going to say a little bit about Vann,” said Martha McConnell, who serves as co-president with the group along with her husband, Jimmy. “We can’t find any of his family that was here after 1820, so that’s probably why it remained unmarked for so long. It was marked with wood and then it deteriorated.”

Jimmy McConnell gave insight into the complicated life of Vann.

“James Vann was only 43 years old, and who knows how long he could have lived and what influences he could have had on people and our nation,” he said.

Before Cherokee removal in the Trail of Tears, Vann, the son of a Scottish trader and Cherokee mother, was a leader of the “young chiefs,” a group who rebelled against the established “old chiefs,” and was known for his immense personal wealth.

He also pushed for the westernization of the Cherokee. Vann allowed Moravian missionaries, who wrote diaries that historians use for insight into the time, on Cherokee land.

He was also a polygamist and known for issues with alcohol,

which historical sources said made Vann cruel to others and may have led to his

shooting.

The Chief Vann House in Chatsworth was originally inhabited by Vann in 1804 and later by his son Joseph Vann. The historic site is now operated by the Georgia Department of Natural Resources and open to the public.

Vann was known for owning and operating a number of taverns along Federal Road, which ran from Augusta to Chattanooga. One of the taverns can still be seen in Forsyth County.

“The one that was here was moved across the road and used as a workshop [or] farm building for about 100 years, then the city of Cumming moved it to the Cumming Fairgrounds and renovated it,” Martha McConnell said. “So, it’s down there for everybody to enjoy it.”

After his death, Vann’s body was said to be buried with an unflattering epitaph near a “pale fence painted black.” Members of the historical society were able to find the approximate location of the grave using old photographs and metal detectors.

“They metal detected the whole cemetery, and they came to this spot and there were ‘pings’ all around then down the mill,” Martha McConnell said. “We dug around just enough to find four nails. At 10-inch intervals, we found homemade nails that appear to be from that period the way they’re constructed.”

George Pirkle, also a member of the historical society, said the group had to be careful due to concerns about preserving the site and federal laws.

“There were several years where we tried to decide, ‘Should we put anything there,” because we were so afraid somebody would … come in and just dig it up,” Pirkle said. “Well, there’s nothing there. There might be a bullet, but we’ll never know because as you know, the penalty for exhuming … Native American remains is they will throw you beneath the prison.

“All we could do is scrape the ground very lightly to see if we could find anything.”

The stone used for Vann’s memorial was from the former farm

of Cherokee Chief Rising Fawn, who also resided in present-day Forsyth County.

The marker for Vann’s grave wasn’t the only historic marking by the group on Saturday.

A dedication was held for a sign in Poole’s Mill Park memorializing Welch’s Mill, which was built by Cherokee leader George Welch. Metal posts at the side of Settingdown Creek are all that remain of the mill.

“It really celebrates the foresight of George Welch for building the gristmill to begin with,” said Jimmy McConnell. “Then, it had a sawmill attached to it that was driven by the same waterwheel. Later there was a stamp mill and card mill.”