Charlotte Dillard has one of those syrupy drawls that could make a recipe read aloud sound about as good as whatever sizzles in the skillet.

After just a few minutes of conversation, it is funny how much Dillard, 59, a former Forsyth County resident, sounds like Southern cooking diva Paula Deen -- right down to a pinch of "y'all" and a dash of belly laughs.

"I am not believing this," Dillard said on a recent afternoon, chuckling loud and long at a suggestion she's heard before.

"A lady the other day from Boston called me from a museum and we talked for a long time. She said, 'Charlotte, don't let me hurt your feelings, but you sound like that lady on that cooking show down there.'"

Over the past couple of years, Dillard has done her share of talking to folks from Boston and beyond.

And there's liable to be a lot more talking to come.

Dillard, who now lives in the northeast Mississippi town of New Albany, has become something of an amateur historian and self-educated expert on John Parker Boyd, a brigadier general in the War of 1812.

"I've always liked history," Dillard said. "But I've never really studied up on things like I have this."

Dillard's own story might one day read like this: How a Mississippi mother with a voice like Savannah restaurateur-turned-television star became an expert on a Massachusetts-born soldier of fortune who's been dead for nearly 178 years.

And it all started when she walked in the Cumming Goodwill store scouring shelves for old cookbooks.

What she found instead -- a set of two pocket-sized Bibles, one for $3.03 and the other $4.04 -- inexorably linked a modern-day treasure hunter with a 19th century soldier of fortune.

"It seems like my life has evolved in with his family and his life," Dillard said. "And when you study and research people from the past, that's what happens. My husband teases me and says that John Parker Boyd is the other man in my life."

The other man in her life

Boyd was born in 1764 in Newburyport, Mass., and went on to become a noted serviceman who commanded army brigades in the 1811 Battle of Tippecanoe, where U.S. forces defeated Shawnee Chief Tecumseh.

He also served in the U.S. Navy, as a soldier of fortune in India and as an Army officer throughout the War of 1812.

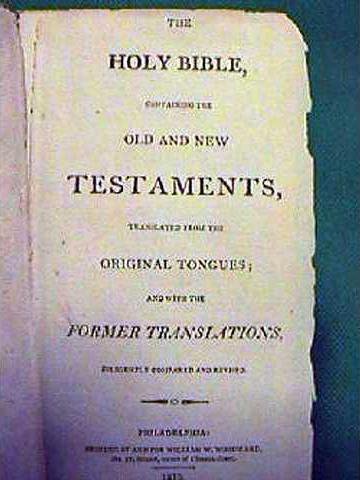

The Boyd Bible that Dillard found at the Cumming Goodwill was printed in 1810 in Philadelphia. It bears an inscription dated 1830, the year of Boyd's death, bestowing the Bible to his niece Symphonia A. Little in Boston.

The books, divided among Old and New Testament, are about the length and width of a $1 bill, and the Dillards keep them in a bank lockbox.

"It's in pretty good condition," Dillard said. "We don't handle it a lot at all. And when we do handle it, we handle it with white cotton gloves. Of course, we try to be really careful with it. The covers are loose on it, but we've been told not to have it rebound.

"Every now and then we go get it. Some family will be coming in or something and we'll go get it and bring it home."

Besides museum officials and family members, Dillard's extensive Boyd research has attracted inquiries from Daughters of the American Revolution chapters and War of 1812 societies, a Syracuse University professor and newspaper reporters from Tupelo to Newburyport.

"The girl asked me about it," Dillard recalled of her recent interview with a Newburyport Daily News reporter.

"She said, 'Well how do you feel about John Parker Boyd?' And I laughed, you know, and I said that when I die and go to heaven, after I see my family, I want to meet John Parker Boyd."

On this side of the hereafter, Dillard's tenacious pursuit of all-things-John Parker Boyd has even piqued the interest of Jay Williamson, curator at the Historical Society of Old Newbury, in Boyd's birthplace.

"He's rather unknown here," Williamson said. "It's not a name we'd really heard of until we got the call about a year ago."

Williamson said he's had a couple of conversations with Dillard about the Boyd Bible. In historical circles it's best described as a "relic," he said, or a common item with ties to the past, sort of like "George Washington ate with this spoon" kind of thing.

"To me it seems like this find opened a wellspring of history that this woman never knew existed within herself," Williamson said.

The first guy matters

The dual ironies that her accent is a dead ringer for Deen and she was on a hunt for old cookbooks when she ran across the Boyd Bible are not lost on Dillard's 46-year-old husband Tim.

"She's definitely a Southern belle without a doubt," he said. "She's collected cookbooks all her life, and we probably have way too many. But we have thoroughly enjoyed the study that we've done with the Bible. It's just been something new every month.

"I think the reason she says that he's the second man in her life is because she's spent so much time doing this. She says, 'Tim I hope you don't feel like I'm neglecting you.'

"I say, 'Oh, no honey, you just go on ...'.

"Nah, it hadn't been that bad. I love her and I'm glad that she has a passion for that because it is something that needs to be told. And it's a part of history."

During the four years and change that the couple and their son Andy lived in Forsyth, they often hit up estate sales and thrift stores, looking for deals.

Once, Tim Dillard recalled, on a drive through Cumming, they passed a yard sale, and though "we usually don't do yard sales," his wife told him to turn around.

From the road, she had spotted three pieces of pottery sitting on a table. The folks wanted $10 for the lot, he said, and his wife told him to pay it -- right then.

The three pieces for $10 turned out to be highly collectible Hull pottery, valued at $1,300.

"She knows what to look for," he said. "She has an eye for it and she sees it."

On another treasure hunt north of Dawsonville, the couple found a $30 Samuel Ward Stanton lithograph of "City of Montgomery." Stanton was the accomplished painter who died on the Titanic.

Whether it's Boyd or Stanton or some other long-dead fellow who finds his way into the couple's home, Tim Dillard pretty much knows his place.

"I'm always the first guy. So that's what matters."

'Oh Dear Lord'

It was a cold and rainy fall afternoon more than three years ago when the Dillards stopped to browse around the Cumming Goodwill for cookbooks.

At the time, they lived off Browns Bridge Road and attended Coal Mountain Baptist Church. Tim Dillard worked in sales for Alley Cassidy Brick Co., and his wife had been out with him on a job.

While she was working on her recertification as an independent insurance agent, Charlotte Dillard had been perusing thrift stores and estate sales for old recipe books. She wanted to compile her own volume, in her spare time.

"I was just in there because that's where you find the good ones," she recalled. "When people don't want it any more, they take a lot of things to the Goodwill. ... We figure that's probably how the Bible got there, that someone had it and didn't know what they had."

The couple didn't really know what they had with the Bible, either, until much, much later.

"When we found it, I didn't know for a long time what I had," she said. "I just went home and put it in the bookshelf. And one day at home I was dusting and it was in the bookshelf. I got it out and I opened it up.

"I went to the computer and I just typed his name in. And when I did, all of these things just popped up. I just leaned back and I said to myself, 'Oh, Dear Lord, what do I have?'"

After that, she simply started reading everything she could find about Boyd and calling folks who might know more.

And the rest, as they say, is history.

In Dillard's research she discovered that the Boyd genealogy line spans from

Massachusetts and Maine to Georgia and Mississippi.

Strangely enough, the Boyd family owned plantations near Natchez and Boyd's niece Symphonia, who inherited the Bible, wound up drowning in the Mississippi River.

Still, no one knows how Boyd's Bible landed on a thrift store shelf in Forsyth County.

"I wish I could tie it all together," she said.

And if anybody can, it would seem she's the one to make the connection.

"Just imagine for the two Bibles to have stayed together for almost 200 years, I would have thought they would probably gotten separated," her husband said.

"And how in the world ... we wish we'd known how they ended up in Cumming, Ga.

That's really a mystery we'd really like to know. How they ended up there."

In the meantime, even though $4 a gallon gas has curtailed her treasure-hunting excursions, Charlotte Dillard may make the hour-drive from New Albany to Memphis, looking for new old treasures.

"I used to like to go to Memphis to the estate sales, midtown, down close to the river," she said.

"The good estate sales in Memphis you go to midtown. That's where you find the old stuff."